The first five posts laid the foundation for understanding why the world feels dense, fast, and tightly connected. We explored the sense that something in the operating logic of civilzation is shifting. We looked at phase transitions, the four-stage pattern that repeats across history, and the seven domains that structure civilization. The last post introduced the three deep drivers that push civilizations across thresholds: growing convergence, system-shaping technologies, and the acceleration of knowledge. Taken together, they help explain why pressure builds, why systems couple, and why some ages move differently than others.

Before we explore whether the present moment resembles the early stages of past transitions, we need a way to read the system as it is now. Large forces alone are not enough. To understand whether pressure is building, we need a simple method for sensing when foundational domains are becoming more reactive, when they begin to shape one another, and when the distribution of activity becomes unbalanced. That is the purpose of two gauges in this framework: Total Systemic Domain Score (TSDS) and Activation Dispersion (AD). They are not forecasts. They make complexity legible in human terms.

Most people do not think in terms of domains or drivers. They experience change in daily life: new tools appear at work, expectations rise, global tensions spill into local conversations, or familiar institutions struggle to keep pace. TSDS and AD help translate that experience into a clearer picture of where we are in the arc of change. They offer a simple way to understand how active the system is overall and how that activity is distributed across the seven domains.

TSDS reflects the level of activation in each foundational domain. Activation describes how much each domain is moving, how quickly it is changing, and how strongly it interacts with others. A short table makes the idea easier to see.

Some ages show movement in only one or two domains. Others experienced broader activation across several, but never all seven. TSDS adds these activation levels to create a single view of system momentum. A high TSDS is not good or bad on its own. It simply tells us that several foundational parts of civilization are in motion at the same time. When TSDS rises, life typically feels more compressed and more uncertain because multiple forces are evolving together.

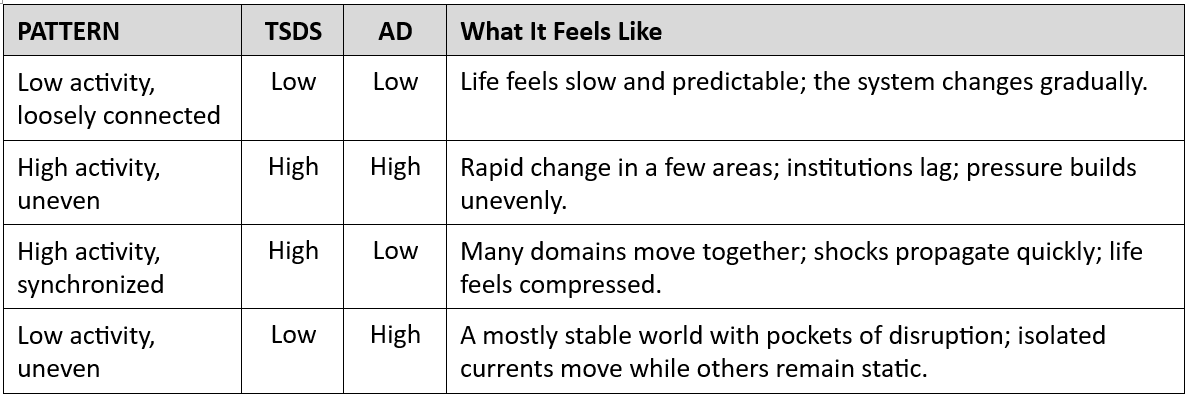

But overall pressure is only part of the story. Activation Dispersion (AD) describes how evenly or unevenly activation is distributed across the domains. Some ages are defined by concentrated movement in a few domains. Technology or economics may surge while geopolitics, philosophy, or society move slowly. These periods produce high AD because activation is uneven. Other ages appear to have low AD, but this value can reflect two very different realities. In early ages, low AD simply meant everything was structurally quiet; the domains were equally inactive and loosely connected. In later ages, low AD can mean the opposite: many domains accelerating at once and becoming interdependent. These two conditions feel nothing alike. One produces stability, the other produces fast propagation.

AD functions as a conceptual gauge rather than a statistical measure. It reveals the shape of systemic pressure: whether activation is concentrated in a few domains or shared across many, and whether changes remain local or spill outward.

A table helps show how AD means different things in early and later ages.

When combined with TSDS, AD offers a simple view of how life feels inside a system.

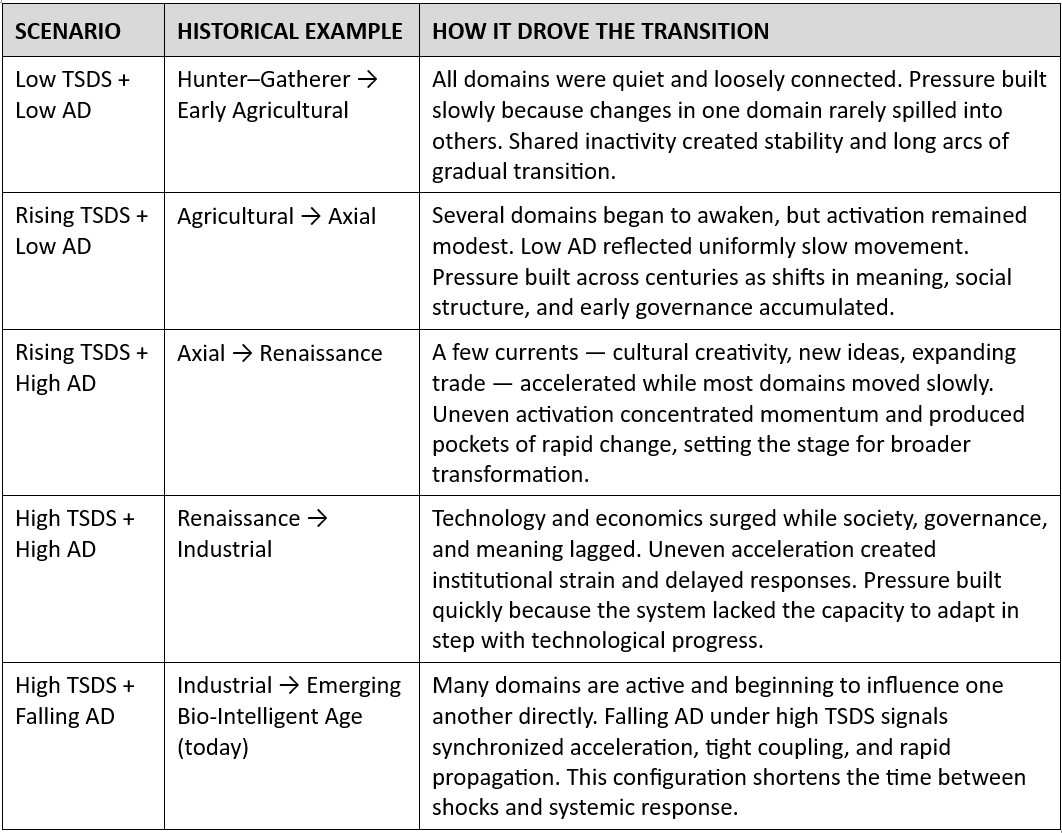

Understanding these simple patterns helps clarify why different ages felt so different and why today feels unfamiliar. In early ages, low TSDS and low AD created long periods of stability. Domains moved slowly and rarely interacted. Pressure built gradually, which is why the Agricultural and Axial shifts unfolded over centuries. As TSDS rose and AD increased, uneven activation produced periods of friction and tension. A small set of currents — such as cultural creativity, new ideas, and expanding trade — accelerated while others moved slowly. These uneven patterns helped set the stage for the Renaissance.

The Industrial Age began with high TSDS and high AD. Technology and economics surged while society, geopolitics, and philosophy lagged. This uneven configuration concentrated pressure. Institutions struggled to keep pace. Delayed adaptation amplified social stress. Even though the domains were not synchronized, activation in a few areas was powerful enough to destabilize the system. High AD did not reduce pressure; it intensified it by creating gaps between fast-moving and slow-moving parts of life.

Today’s emerging configuration is different. TSDS is high because many domains are active at once. At the same time, AD appears to be falling because domain activity is becoming more synchronized. Science and technology influence geopolitical debates, economic shifts affect societal norms, environmental changes shape geopolitical calculations, and philosophy reopens questions about identity and legitimacy. The system is tightening not because one domain leads, but because several move together. In this context, low AD no longer signals stability. It signals integration and faster propagation of change.

The interplay between TSDS and AD becomes clearer when viewed across history.

These patterns show that transitions emerge whenever TSDS reaches levels that apply sustained pressure, regardless of whether AD is high or low. In early ages, pressure accumulated slowly because domains were loosely connected. In the Industrial Age, pressure rose rapidly because fast-moving currents collided with slower adaptation. Today, pressure spreads quickly because many domains are moving at once.

TSDS and AD do not predict events. They do not specify which technologies will succeed or which political choices will prevail. Their purpose is to help us understand the character of the moment: how much activity is building and how that activity is distributed. They help distinguish ordinary turbulence from systemic pressure. They offer a clearer picture of whether complexity is rising because of isolated forces or because the architecture of civilization is tightening.

This clarity matters because it shapes how leaders and institutions respond. When TSDS rises, assumptions about the pace of change need to shift. When AD falls under high TSDS, cross-domain impacts become more significant. A change in one part of life no longer stays where it began. Institutions that recognize this coupling adapt more effectively than those that treat changes as isolated.

These gauges also help explain why the present moment feels different from the recent past. TSDS is high because many domains are active. AD is falling because movements in one domain increasingly influence the others. The system is tightening, and the effects are visible across daily life.

In the next post, we will test this framework against four major transitions: from Hunter–Gatherer to Agricultural, from Agricultural to Axial, from Axial to Renaissance, and from Renaissance to Industrial. Viewed through TSDS and AD, these transitions reveal how pressure accumulated and how changes in activation gradually reshaped the relationships between domains, setting the conditions for new forms of order to emerge. These patterns help illuminate what today’s signals might mean and what it looks like when a new operating logic begins to emerge.

THE SERIES TO DATE

- When Systems Turn Over

- Why Everything Feels Like It’s Changing At Once

- How Big Shifts Unfold — And Where We Are Now

- Why No Single Force Changes The World

- The Three Drivers That Push Civilizations Across Thresholds

Discover more from Reimagining the Future

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

[…] three drivers that push systems toward those moments. With that groundwork in place, I introduced a pair of gauges that make those movements easier to see. In this post, I describe the gauges in greater detail. […]

LikeLike

[…] Reading The Pulse Of A Civilization In Motion […]

LikeLike

[…] Reading The Pulse Of A Civilization In Motion […]

LikeLike

[…] Reading The Pulse Of A Civilization In Motion […]

LikeLike

[…] Reading The Pulse Of A Civilization In Motion […]

LikeLike

[…] Reading The Pulse Of A Civilization In Motion […]

LikeLike