The earlier posts introduced the sense that the world’s operating logic is beginning to shift, explored what compression feels like in daily life, and laid out the four-stage pattern that has shaped every major transition in history. Post Four explained why those transitions do not come from singular breakthroughs but from the interaction of multiple domains moving together. Before we can measure that interaction in today’s world, we need to understand the deeper forces that give convergence its power. These forces have shaped every civilizational transition across the long arc of history. They determine when pressure accumulates, how tightly systems couple, and what pushes society toward a threshold.

WHY THRESHOLDS NEED MORE THAN MOMENTUM

Every era contains moments of brilliance, invention, conflict, and social change. Most pass without altering the deeper structure of civilization. Thresholds — moments when a new operating logic emerges — require more. They appear when three larger drivers begin reinforcing one another: domain convergence, the emergence of general-purpose technologies, and the expansion and diffusion of knowledge. Each driver matters on its own, but history reveals a deeper pattern. Their involvement has grown across the ages, raising complexity step by step. Transitions occurred even when these drivers were only partially aligned. None were ever fully synchronized. That is what makes the present moment unusual.

Some historians may point to other forces — demography, institutions, energy, conflict, religion, or capitalism — as engines of change. All of these matter, but none fall outside the seven foundational domains that structure civilization. Demography lives within society and economics. Institutions belong to governance and philosophy. Energy is part of the material loop that connects environment, technology, and economics. Conflict reshapes geopolitics and technology. Religion and ideology sit inside the meaning loop. Capital and finance operate within economics and geopolitics. These forces do not sit above or outside the seven domains in this framework; they operate through them. The three drivers simply describe how changes within and across these domains become systemic.

THE FIRST DRIVER: DOMAINS BEGINNING TO MOVE TOGETHER

Convergence is the first and most consistent force in the evolution of civilization. In hunter–gatherer life, domains barely existed as distinct structures; the environment dictated everything. With the Agricultural transition, early economics, social roles, meaning systems, and rudimentary technologies began to influence one another.

The Axial transition saw meaning, geopolitics, philosophy, and early governance interact at a broader scale within regions as diverse as Greece, India, China, and Persia, with transformations emerging independently but in parallel. Some scholars debate the scope and coherence of the Axial transition, but its influence on meaning, ethics, and legitimacy is difficult to overstate. The religions and philosophies that emerged during this period reshaped the inner architecture of civilization and continue to guide moral and institutional life across much of the world. One measure of its influence is the intensity with which Axial meaning-systems have shaped identity and allegiance across history. The scale of conflict carried out in the name of religion is not a reflection of belief itself, but an indication of how deeply these meaning structures became embedded in governance, legitimacy, and collective purpose.

The Renaissance and the Scientific Revolution introduced deeper interplay across science, philosophy, economics, and society. The Industrial transition tied science, technology, society, economics and geopolitics, into a tightly coupled system. Convergence grows across every age, and as more domains activate, the system becomes more interdependent. This rising coupling is the foundation of civilizational complexity.

It is worth naming that this story is not Western by design. The Agricultural and Axial transitions were not Western phenomena; they unfolded across multiple regions and shaped every major civilization. The Renaissance and Industrial transitions began in Europe, but their impacts were global, reorganizing trade, knowledge, governance, and material life far beyond the West. The aim here is not to tell a regional story but to trace the moments when the underlying structure of civilization shifted for humanity as a whole.

THE SECOND DRIVER: TECHNOLOGIES THAT RESHAPE CIVILIZATION

General-purpose technologies (GPTs) have appeared throughout history, and each has reorganized the deeper structure of civilization. Some, such as language and writing, reshaped how people coordinated, stored knowledge, and built the first complex societies. Others, such as the printing press — which reached systemic scale in Europe after 1450, following earlier East Asian inventions — steam engines, and electricity, transformed production, mobility, communication, governance, and daily life. The domains they influence differ, but their effect is consistent: each GPT changes how people work, connect, and make sense of the world by altering multiple parts of the system at once.

What changes across the ages is the speed at which these transformations unfold. Early GPTs took centuries or even millennia to reshape society because knowledge moved slowly, populations were sparse, and domains remained loosely connected. Later GPTs diffused much faster, altering civilization within decades as knowledge accumulated, communication accelerated, and domains became more interdependent. GPTs do not appear out of nowhere. They emerge from capabilities that came before them, and once they arrive, they accelerate those capabilities in return. This feedback loop strengthens with each age and helps explain why the impact of GPTs grows more rapid and more systemic over time.

A new wave of GPT-level technologies may be emerging today: artificial intelligence, synthetic biology, and humanoid robotics. It is too early to know which of them, if any, will ultimately reshape civilization to the degree previous GPTs have. What matters for this analysis is that GPTs historically appear only after multiple domains reach certain thresholds, and when they do, they change how quickly systems evolve and how tightly domains begin to interact.

THE THIRD DRIVER: HOW KNOWLEDGE ACCELERATES ITSELF

Knowledge is the quiet accelerant behind every major transition. Language and writing reshaped how communities stored, shared, and combined ideas, making knowledge durable and cumulative for the first time. Their impact unfolded slowly, but they created the conditions for civilization itself. The Axial transition expanded the scope of knowledge through codified meaning systems. The Renaissance accelerated knowledge through experimentation and the printing press, which made ideas portable, combinable, and difficult to contain.

The Industrial transition applied and scaled the scientific method — alongside mass literacy and engineering practice — allowing knowledge to grow rapidly and spread widely. Each transition shows knowledge moving faster and reaching further than in the one before it. As knowledge expands, it creates the conditions for new technologies to emerge, and those technologies accelerate knowledge in return — a feedback loop that grows stronger across the ages.

HOW THE THREE DRIVERS GREW ACROSS THE AGES

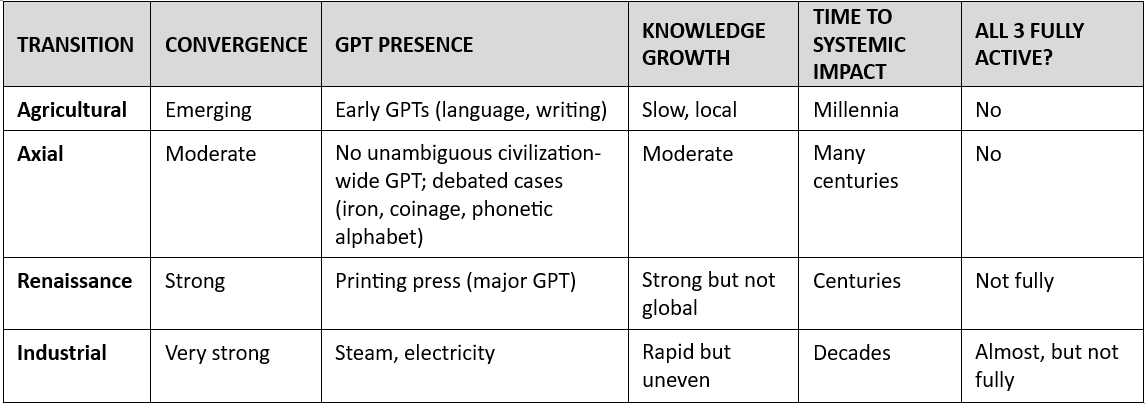

A clear pattern emerges when these drivers are viewed together. Across the four historical transitions, the involvement of all three drivers increased. Convergence strengthened as more domains activated. GPTs appeared in every age, but the time it took for them to reshape civilization shortened dramatically as knowledge grew and communication expanded. Knowledge itself accelerated with each era, moving from slow, local inheritance to global, combinable flows. Yet the drivers never aligned fully at the same time. Their partial alignment explains why each transition was powerful but incomplete — strong enough to reorder civilization, but not enough to synchronize it globally. The pattern becomes clearer when viewed side by side:

The rise of the drivers mirrors the rise of complexity itself. Each transition reorganized more of civilization because each emerged from a stronger combination of the drivers than the one before it.

THE KNOWLEDGE–GPT FEEDBACK LOOP

A deeper story runs through this pattern. Knowledge grows slowly at first. Language and writing made it durable, cumulative, and shareable across generations. As knowledge accumulated, later GPTs such as printing, steam, and electricity emerged into a richer environment and accelerated knowledge in return. This creates a feedback loop: knowledge enables new forms of capability, and GPTs amplify the speed and reach of knowledge itself. Convergence strengthens as both intensify. The loop appears to emerge faintly in the Agricultural and Axial transitions, becomes clearer in the Renaissance, and gains full strength in the Industrial age. The system becomes more tightly coupled because knowledge and capability feed one another.

WHY THESE DRIVERS MATTER TODAY

Recent years show an unusual alignment of the three drivers. Convergence now appears to span all seven domains at once. Knowledge has become far more global, instantaneous, and combinatorial for a historically unprecedented share of humanity. And while it is too early to know which of today’s technologies will demonstrate the kind of system-level impact seen in past GPTs, several are advancing quickly enough to influence every domain simultaneously. The drivers are not just active; they appear to be reinforcing one another in ways that echo the early stages of past transitions. This does not guarantee a threshold, but it creates stronger conditions for systemic acceleration than any earlier period. Understanding these drivers helps explain why the world feels dense, fast, and tightly connected — and it prepares us to use the gauges that make these pressures visible.

LOOKING AHEAD: MEASURING THE PRESSURE IN THE SYSTEM

Now that the drivers are clear, the next step is to understand how their combined pressure shows up in measurable form. In the next post, I turn to two simple gauges that help illuminate this moment — Total Systemic Domain Score (TSDS) and Standard Deviation (SD). They do not predict the future, but they help distinguish between noise and signal in a tightly coupled world.

WHAT THIS MEANS FOR US

The history of these drivers reveals a long, steady arc of rising complexity. Civilizations do not shift because of isolated inventions or singular ideas. They shift because convergence strengthens, system-shaping technologies reorganize entire systems, and knowledge accelerates to the point where domains cannot remain separate. The drivers have been intensifying for thousands of years. Today, they appear more aligned than at any point in the past. Recognizing this pattern helps us see why the present moment feels different — and why the future may not unfold the way the past has.

THE SERIES TO DATE

- When Systems Turn Over

- Why Everything Feels Like It’s Changing At Once

- How Big Shifts Unfold — And Where We Are Now

- Why No Single Force Changes The World

Discover more from Reimagining the Future

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

[…] across history, and the seven domains that structure civilization. The last post introduced the three deep drivers that push civilizations across thresholds: growing convergence, system-shaping technologies, and […]

LikeLike

[…] life, the forces that move within them, the thresholds that mark historical turning points, and the three drivers that push systems toward those moments. With that groundwork in place, I introduced a pair of […]

LikeLike

[…] The Three Drivers That Push Civilizations Across Thresholds […]

LikeLike

[…] The Three Drivers That Push Civilizations Across Thresholds […]

LikeLike

[…] The Three Drivers That Push Civilizations Across Thresholds […]

LikeLike

[…] and showed why no single force ever moves a civilization forward on its own. We examined the three drivers that push societies across thresholds and built gauges that make systemic pressure legible. Using […]

LikeLike

[…] The Three Drivers That Push Civilizations Across Thresholds […]

LikeLike