Civilization’s great shifts are the moments when continuity fails and a new order takes shape. Each historical age reached a point where the old logic could no longer hold, and pressures converged into a transformative release. By examining four major transitions – from Hunter–Gatherer to Agricultural, Agricultural to Axial, Axial to Renaissance, and Renaissance to Industrial – we can see how rising Total Systemic Domain Score (TSDS) and changing Activation Dispersion (AD) signaled that a threshold was near. Some transitions unfolded slowly over millennia, while others struck within a few centuries. In each case, the build-up of energy and imbalance hit a critical point, and society crossed into an irreversible new configuration that only in hindsight feels inevitable.

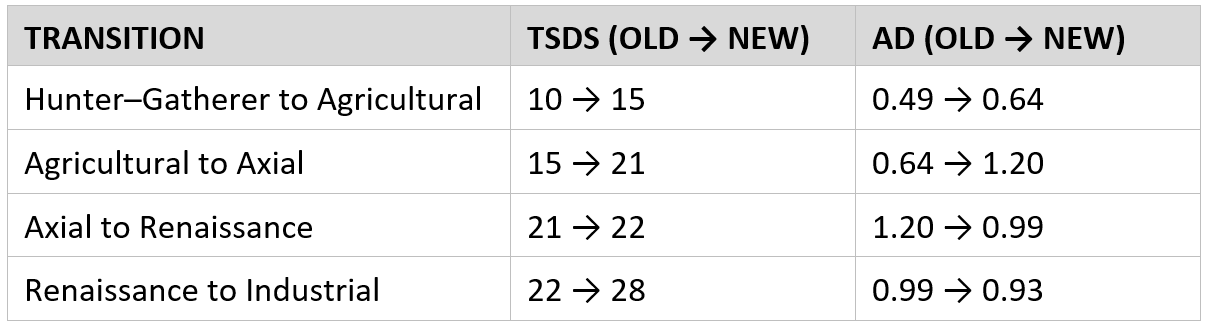

To ground each transition, the table below summarizes the system’s vital signs at the end of the old age and the emergence of the new one – namely the TSDS (overall activation across seven domains) and the AD (how that activation was distributed). Higher TSDS means more domains of life were active; higher AD means one or two domains were far ahead of others. These gauge readings capture the late-stage signature of each age, just as it approached its turning point:

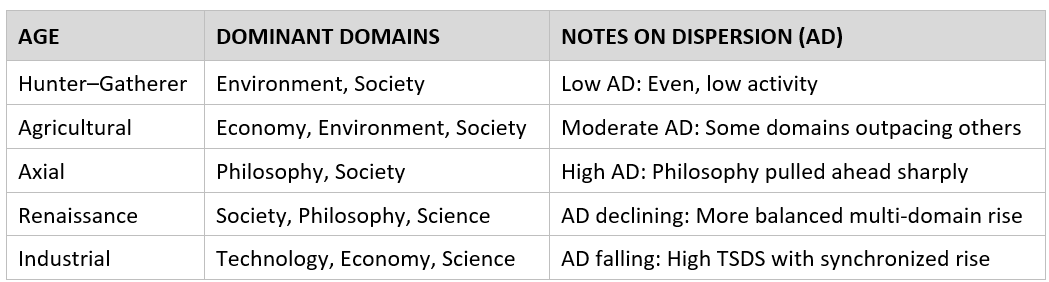

While the gauges show when a system reached its limits, they don’t reveal why each age became unstable. The table below highlights which domains were most active near the end of each age, helping explain what kinds of pressures drove each transition — and how concentrated or diffuse that activation was across the system.

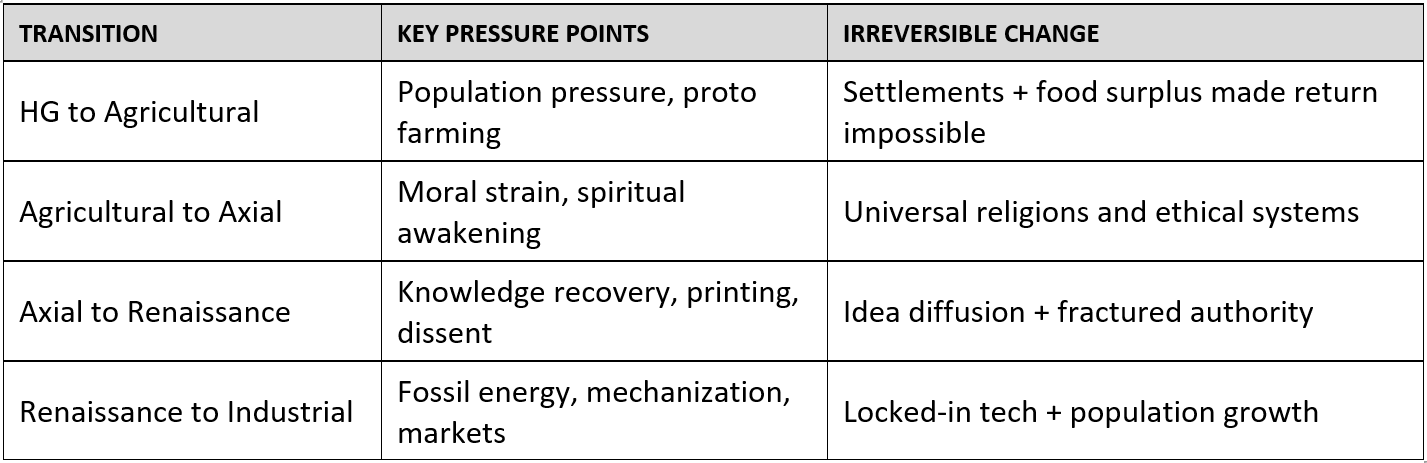

Each transition was a threshold crossing. Below, we explore each one – the late-stage profile of the age that was ending, the internal tensions that built up, the domain shifts that created instability, how TSDS and AD moved as the system hit its limit, what made the break with the past irreversible, and what new structure emerged on the other side.

FROM HUNTER–GATHERER TO AGRICULTURAL SOCIETY

By the end of the Hunter–Gatherer age, human society had a low-energy but stable simplicity. Life was organized in small bands living within nature’s limits. The TSDS was about 10, reflecting that only a few domains (like the environment and basic social structures) actively shaped daily life. AD was low (≈0.49), meaning whatever activity existed was spread evenly – no single aspect of life dominated the rest. In this late hunter-gatherer phase, change was slow and local. People adapted to their environments incrementally, and for a long time the system absorbed pressures without drastic reorganization. There was little surplus energy in the system to drive major innovation or upheaval; pressure accumulated almost imperceptibly. Yet, under the surface, conditions were gradually shifting.

Tensions began to build as the climate warmed and resources fluctuated at the end of the Ice Age. Populations in some regions slowly grew, and communities started probing the edges of their old nomadic lifestyle. A few domains showed flickers of new activity: for example, early technology (stone tools, fire use, simple plant cultivation) and social learning allowed humans to extract more from their surroundings. These small innovations were modest on the scale of TSDS, but they introduced an imbalance – a hint of specialization that the old nomadic framework couldn’t fully support. Over generations, people in fertile areas began experimenting with planting seeds and taming animals. The environment and economy formed a new feedback loop: humans learned to intentionally shape nature to produce food. This was a slow revolution – energy and population slowly accumulated over millennia until new institutions could form. But it set the stage for a fundamental shift. Communities that once simply followed game and seasons were putting down tentative roots. The AD of the system crept up as these changes took hold – a sign that one part of life (food production know-how) was growing out of step with the old norms.

As TSDS rose toward 15 with more domains becoming relevant to everyday life, the system approached its threshold. The tipping point wasn’t a single year or invention, but by the time agriculture became a reliable strategy, the change was irreversible. Cultivation and herding created food surpluses, which supported larger settlements and higher populations than the hunter-gatherer life ever could. Once people settled in farming villages, there was no going back – their numbers and new dependencies wouldn’t allow a return to wandering foraging without mass starvation. In effect, the system’s internal structure had flipped: where nature once entirely dictated human movement, now humans began reshaping nature to suit their needs. The threshold was crossed when the old equilibrium (small, mobile bands) collapsed under the weight of these new practices. The Activation Dispersion spiked to ~0.64 by this point – evidence that a couple of domains (the environment-economy duo) now drove much of life, forcing all other aspects to adapt or be left behind.

On the other side of this threshold emerged the Agricultural Age. Its new structure was defined by domestication anchoring human society. Humanity had learned to domesticate plants and animals, allowing permanent settlements and a predictable food surplus. Land and labor became the organizing principles of life, replacing the flexible foraging bonds with fixed villages, fields, and pastures. In this agrarian world, knowledge became less embodied and local – some of it was now stored in the environment itself, in the form of sown fields and bred livestock. Power and social organization also began to change; those who controlled fertile land or stores of grain held new influence. This was still a simple society by later standards – TSDS 15 indicates that only a few domains (primarily environment, economy, and basic social structures) were strongly active. But it was decidedly more complex than the hunter-gatherer era.

A partial convergence had taken place: nature and human economy were now fused in a cycle of sowing and reaping. Communities grew into villages and early cities; networks of exchange formed; rudimentary institutions and shared cultural practices emerged to manage settled life. The moral dimension of this new power over nature also appeared as a tension – for the first time, humans faced questions about exploitation versus stewardship of the environment. That question would echo through every future age, but the Agricultural Age had set the template. A new pattern of life had emerged, and the world would not return to the old one.

FROM THE AGRICULTURAL AGE TO THE AXIAL AGE

Agrarian civilization brought stability, but over time it also generated pressures that pushed society toward a new threshold. By the late Agricultural Age, TSDS had risen to about 15 – more domains were in play than before, including organized economies, stratified societies, evolving political orders, and nascent philosophies. However, progress across these domains was uneven. AD climbed to roughly 0.64, reflecting growing divergences: some aspects of life (like economy and social hierarchy) had become quite complex, while others (like science and technology) remained rudimentary. In this era, land and labor organized society and life was still largely constrained by local, slow-moving factors. Pressure built gradually – kingdoms and trade networks expanded, cultures refined agriculture and craft, populations slowly increased. For generations the system adapted within the agrarian paradigm. But internal tensions were accumulating beneath the surface, setting the stage for the Axial Age’s upheavals.

One key tension was social and moral strain. Agrarian empires and city-states created new scales of human interaction – laws, classes, taxes, and wars – that the old mythologies and tribal customs struggled to legitimize. Inequalities of wealth and power grew alongside the granaries. People began to sense gaps between material advancement and moral order. The moral tension introduced by humanity’s new power – the question of how to reconcile exploitation with ethical stewardship – became harder to ignore. At the same time, ordinary individuals lived in the shadow of vast structures (temples, monarchies, armies) that promised cosmic or divine justification. Over centuries, doubt and spiritual restlessness mounted. The cultural current within society – latent in early agrarian life – started to awaken as people sought meaning beyond the ancestral gods tied to nature’s cycles.

This brewing dissatisfaction set off a remarkable domain movement that ultimately defined the Axial Age: a surge in philosophy and religious thought. Across the Old World, roughly in the middle of the first millennium BCE, a burst of new ideas came forward to reorder society’s guiding values. Thinkers and prophets from many regions began asking fundamental questions – What is the right way to live? What is the nature of justice, of the soul, of the divine? – and their answers catalyzed new belief systems. The Axial Age was essentially a great awakening of reflection: ethics, law, and philosophy took center stage and started to reorder society. Crucially, this wave of ideas far outpaced the material domains’ development. In terms of our gauges, TSDS jumped to ~21 by this era’s peak, indicating a higher overall activation of civilization. But that energy was distributed in a lopsided way – AD spiked to about 1.20, the highest unevenness on record. One domain – the realm of thought and meaning – pulled dramatically ahead of the rest. Philosophy and faith ignited like a brushfire, while technology, economy, and political structures changed more slowly. The system stretched in multiple directions at once. In practical terms, the world was seeing a moral and metaphysical reordering without an equivalent structural overhaul of daily life. This created instability: ideas moved faster than institutions could absorb them.

As the Axial Age progressed, the tension between new ideals and old realities often erupted. The high AD meant society’s fabric was pulled taut – one tug could tear it. We see this in history as periods of crisis and transformation. For example, new universal religions challenged established authorities; philosophical principles (like Confucian ethics or Greek rationalism) questioned traditional norms. Revolts, reforms, and even collapses of old orders accompanied the spread of Axial ideas. In some regions, empire-builders tried to harness the new ideologies (converting to a new faith or enshrining ethical philosophies into law) to hold society together. But the old equilibrium was gone – a purely agrarian, king-and-temple order could not be put back in place once people’s conception of the world had broadened. The transition crossed its point of no return when Axial ideas became mass movements – when Buddhism, Confucianism, Judaic monotheism, Greek philosophy, and other Axial thought-systems took root among populations. At that point, rulers and communities had to reorganize; new institutions emerged, built around shared ethics and transcendent beliefs rather than just crops and tribute.

The threshold was crossed piecemeal in different places (there was no single global “Axial year”), but collectively the mid-first millennium BCE marks the break into a new age. What made it irreversible was that human society had acquired a transcendent blueprint – enduring philosophies and religions that people now used to judge and shape worldly affairs. The concept of a higher law or universal truth introduced by Axial thinkers meant that future societies, however technologically limited, would never again be only collections of farmers ruled by warrior-kings. A new structure had crystallized: one where society was anchored by shared ideas and moral codes. In the aftermath, large civilizations coalesced around the teachings of prophets and sages. Ethical and philosophical frameworks became the glue for empires and cultures – for example, imperial laws grounded in Confucian morality, or the spread of Buddhist and later Christian values providing common identity across diverse regions. In short, the world after the Axial transition was organized by ideas as much as by agriculture. This doesn’t mean material life stopped mattering, but the organizing logic shifted: legitimacy and social order were now tied to abstract values and cosmologies. The Axial Age’s late signature – high TSDS and peak AD – reflects a civilization in flux, but out of that flux emerged a more expansive civilizational mindset. Humans now lived not just in a physical landscape of fields and rivers, but in a conceptual landscape of philosophies and faiths that transcended local life.

FROM THE AXIAL AGE TO THE RENAISSANCE

The Axial Age had unleashed powerful ideas, but it did not instantly create a balanced or highly dynamic society. In fact, after the initial Axial bloom, history entered a long phase where those new philosophies slowly sank in while other domains caught up. By the later centuries of the classical era (and into the medieval period), the wild inequality of the Axial surge began to level off somewhat. TSDS remained relatively high (~21→22), indicating that many domains were active to some degree. But crucially, AD started to decline from its peak – falling to around 0.99 by the threshold of the Renaissance. This downward shift in AD meant that the extreme imbalance was easing – science, technology, economy, and politics were gradually advancing and narrowing the gap with philosophy and society. In the medieval world, for example, we see incremental improvements in farming technology, the spread of religions providing broad social cohesion, and political systems slowly adapting (feudal structures, legal codes influenced by religious ethics, etc.). Yet, life in 1400 CE was still far less dynamic than it would become by 1700. The late Axial pattern was one of partial convergence – multiple domains were active but not in sync. Much of the medieval order tried to uphold the Axial ideals (a unified Christendom or Islamic golden age drawing on moral philosophy, for instance) while still grounded in agrarian economics and limited science. Pressure for change built steadily but quietly through these centuries, as knowledge accumulated and small innovations popped up within the constraints of the old order.

By the eve of the Renaissance, signs of strain and opportunity were emerging together. Internal tensions had mounted in the late medieval system: population growth was straining agrarian production, plagues and crises (like the Black Death) were undercutting feudal structures, and the once-unifying religious authorities were facing corruption and dissent. Meanwhile, new sparks were appearing – bits of ancient scientific knowledge were rediscovered, merchants were widening trade routes, and technologies like improved ship designs and printing were on the horizon. Currents of knowledge and exploration began to stir, setting the stage for a broad awakening. When the Renaissance arrived (roughly 14th–16th centuries), it represented the system finally crossing a threshold into a more connected, fast-moving mode. Several domains suddenly ignited in close sequence: artistic expression and humanism flourished, scientific inquiry was reborn, and social thought embraced classical learning and individual potential. Curiosity reconnected art, science, and humanism during this period, breaking the intellectual monopoly of medieval dogma. Perhaps the single most pivotal trigger was the invention of the printing press, which diffused knowledge at a geometric rate. Printing enabled ideas to travel and replicate far beyond their point of origin, eroding the old gatekeepers of information.

As these forces gained momentum, TSDS inched up to ~22 – a modest increase, but what matters is how the composition of that activity changed. The Renaissance saw multiple domains rising in concert: early in this age, society, philosophy, and science were leading the charge, sparking new ideas and challenging old beliefs. Later in the period, technology, economics, and geopolitics accelerated as well, with inventions, oceanic exploration, and emerging market economies. This multi-domain activation is reflected in the drop in AD to ~0.99. Compared to the Axial Age’s wildly uneven pattern, the Renaissance world was more balanced in its dynamism – no single domain was completely outrunning the others now. Instead, several domains were reinforcing each other: progress in navigation spurred trade; trade created wealth that funded scientific research and artistic patronage; scientific discoveries (like astronomy) challenged religious certainties, sparking social and philosophical debate. The system had become more tightly coupled, and changes in one arena more smoothly spread to others. People of the time felt this as an exhilarating, and sometimes disorienting, sense that everything was changing – from how books were made to how business was done to how nature was understood. In modern terms, civilization’s knowledge infrastructure had upgraded, and diffusion of new ideas accelerated dramatically.

The threshold of the Renaissance can be identified with key inflection points: Gutenberg’s press in the 15th century, Columbus’s voyages at the end of that century, the Protestant Reformation in the early 16th, and the Scientific Revolution soon after. Each of these was a small trigger that unleashed cascading effects (for instance, the printing press fueling religious reform and scientific exchange). By the mid-16th century, it was clear that the medieval order could not be put back together. What made this transition irreversible was the breaking of information monopolies and geographic isolation. Once books could be mass-produced, knowledge would never flow slowly or stay contained again. Once the New World was known, the global web of exchange would only deepen. Once people saw the Church splinter and still thrive in new forms, the idea of a single immutable authority faded. In short, the buffers that once kept the system static – limited literacy, parochialism, rigid institutions – were blown apart. Even resistance (like religious wars or the Inquisition) could at best delay, not prevent, the spread of new ways of thinking. The momentum of multiple domains innovating together ensured that society would not revert to a closed, feudal past.

On the far side of this threshold, we see the Renaissance world and its aftermath (often termed the Enlightenment and early modern period). The new structure was defined by openness, inquiry, and cross-domain fertilization. In everyday life, this meant a person might witness dogma giving way to discovery in various spheres. For example, instead of accepting ancient authorities blindly, people like Copernicus and Galileo used observation and experiment, fundamentally changing the science domain – and with printing, their insights reached across Europe. Diffusion accelerated: an invention in one country was quickly known and replicated in another. Art and literature blossomed with humanist values, influencing social and philosophical thought. Economically, the beginnings of capitalist enterprise and global trade took shape, altering how wealth was created and distributed. Politically, new theories of governance (social contracts, rights, etc.) were debated, undermining the divine right feudal model. In short, the Renaissance transition created a more interconnected, idea-driven civilization, one that was both empowered and destabilized by the speed at which knowledge could spread. By its later years, the system had far less slack than before – changes propagated swiftly, and the stage was set for even greater convergence. The Renaissance Age closed with a world primed for rapid advancement, as evidenced by its TSDS holding high and AD trending downward. The next threshold – into the Industrial Age – would prove even more dramatic.

FROM THE RENAISSANCE TO THE INDUSTRIAL AGE

As the Renaissance gave way to the Industrial age (roughly 18th to 19th centuries), civilization experienced one of the most intense threshold crossings in history. By the late Renaissance/Enlightenment period, TSDS was about 22, near its historical high, meaning a broad array of domains were active and contributing to change. AD had fallen to ~0.99, indicating that several domains were now moving in closer alignment. The world on the eve of industrialization was charged with tightly coupled pressures. Knowledge was advancing on many fronts; economies were becoming global and growth-oriented; political thought (liberalism, democracy) was challenging old regimes; and environmental impact was rising with intensive agriculture and early manufacturing. In Europe and beyond, the “Age of Revolutions” in the late 1700s encapsulated this build-up: cultural, economic, and political systems interlocked and began to lose coherence together. Revolutions in America and France, for example, were not isolated political events – they were entwined with Enlightenment ideas (philosophy domain), economic grievances and opportunities, struggles between social classes, and even the influence of new world silver and global trade. It was as if all the dominos were lined up: a push in one domain readily knocked into the others. Small triggers now had huge effects, a classic sign that the system was nearing a phase transition.

Amid this instability, a breakthrough occurred that would symbolize the Industrial threshold: the harnessing of fossil-fuel energy and mechanization. The invention and improvement of the steam engine in the late 18th century was a relatively modest technical innovation at first glance – a way to pump water from mines. But once refined by James Watt and others, steam power became the tiny spark that set off an industrial inferno. It redefined production and transportation – powering factories, trains, steamships – and in doing so, redefined society itself. Here we see the pattern again: a general-purpose technology ignited a wider convergence. Steam engines and mechanized factories (technology domain) dramatically increased economic output and demand (economics domain); this upheaval in production required new labor structures and led to urbanization (society domain); it also spurred a scramble for resources and markets, shaking up geopolitics (colonial expansion, conflicts for coal and colonies). The initial effect of this takeoff was a spike in imbalance: early in the Industrial Age, technology and economy broke away from the rest, creating sharp unevenness in the system.

In our terms, even though the late Renaissance AD had been under 1.0, the sudden surge of industrial activity likely sent AD upward again in the short term – a few domains were racing far ahead. The world around 1800 reeled under rapid change: old social orders (like the aristocracy) struggled to adapt, philosophical and religious ideas came into question under the onslaught of scientific and material progress, and the environment began to be exploited at an unprecedented scale (mines, pollution) with little immediate response from that domain. TSDS, meanwhile, vaulted upward. By the late Industrial Age, TSDS reached ~28 – the highest yet, reflecting that virtually every domain of human activity had been pulled into the dynamism of this age. No realm of life remained untouched: science was institutionalized and advancing, technology was evolving constantly, economies were booming and busting, societies were being reorganized (from rural agrarian to urban industrial), political revolutions and reforms were widespread, new ideologies emerged, and even the environment was being transformed (forests cleared, rivers dammed). The system’s energy output and complexity hit a peak.

As the Industrial threshold was crossed, irreversibility was painfully clear. Traditional agrarian ways of life collapsed in region after region – artisans were replaced by factories, villages emptied into cities, and local markets yielded to integrated national and global markets. The human population, which had been restrained for millennia by agricultural limits, exploded in number thanks to industrial food production and medicine; this by itself closed off any path back to a simpler era. Perhaps most importantly, the fossil fuel regime locked in a new trajectory: once societies depended on coal and later oil, they could not simply abandon those energy sources without massive disruption. Coal-powered machinery and steam-driven transport vastly outperformed muscle power and wind-sail ships; any nation that failed to industrialize found itself at a stark disadvantage.

Thus, there was no putting the genie back – industrial technology spread because it had to, becoming the new baseline for survival and power. We also see irreversibility in the knowledge domain: the Industrial Age produced an avalanche of scientific understanding (from chemistry to electricity) and technical know-how. This knowledge empowered further change and also armed the populace with new ideas about rights and progress, fueling continuous social demands. By the mid-19th century, even as reactions and backlashes occurred (e.g. the Romantic movement, workers’ movements), the overall direction was set – humanity had left the agricultural world for good. The compression of multiple domains had burst through the old constraints. Reordering was not optional; it was an adaptive response to systemic saturation – the only way forward was through the industrial reorganization of life.

On the other side of this epochal threshold stood the Industrial Age proper – the age that, in many ways, gave birth to the modern world. Its structure was unprecedented: mechanization and the mastery of energy reorganized life itself. In everyday terms, this meant people lived by the clock and the factory whistle; goods were mass-produced and widely distributed via rail and steamship; cities became the dominant centers of population and culture; and new social classes (industrial capitalists, wage laborers) determined the political agenda. Efficiency and expansion became the guiding principles of the age. Underneath, there was a profound convergence of forces: for the first time, multiple deep drivers of change aligned. Science, technology, and the economy worked in tandem – scientific discoveries led to new inventions, which opened new industries and wealth, which funded further science, in a virtuous (and sometimes vicious) cycle. Geopolitics and economics intertwined as industrial nations competed for markets and resources worldwide. Even philosophy and society responded, with Enlightenment ideas about progress and rationality dovetailing with the industrial ethos.

In terms of our gauges, the late Industrial Age saw AD fall back to around 0.93 – a lower dispersion that indicates a more synchronized system. This is because, after the chaotic early Industrial decades, other domains caught up: society enacted reforms, geopolitics settled into a new order of nation-states, science and education spread, and even philosophy grappled with the implications of industrial modernity. By 1900, a more coherent industrial world-system existed, one that was densely interconnected and capable of very rapid change. Pressure now propagated almost instantly – a financial panic or a new theory in one country could quickly affect the whole system. Civilization had never been so energetic, complex, and tightly coupled.

Each age’s end planted seeds for the next, but the Industrial Age in particular demonstrated how far the pattern had evolved. Never before had so many domains been active at such intensity. With a TSDS nearing the upper bounds and many domains in sync, humanity approached a new kind of threshold – one that lay beyond the Industrial. What’s crucial is that by the end of the Industrial transition, the systemic rules of the game had changed: progress itself was now expected to be continuous and accelerating, and the world was knitted into one interacting whole.

Each transition tells a story of mounting pressure, internal misalignment, and eventual rupture. While the details vary, every age crossed a threshold when its structure could no longer contain the forces building within it. The table below distills these moments—what drove the system to its breaking point, and what made the resulting shift irreversible.

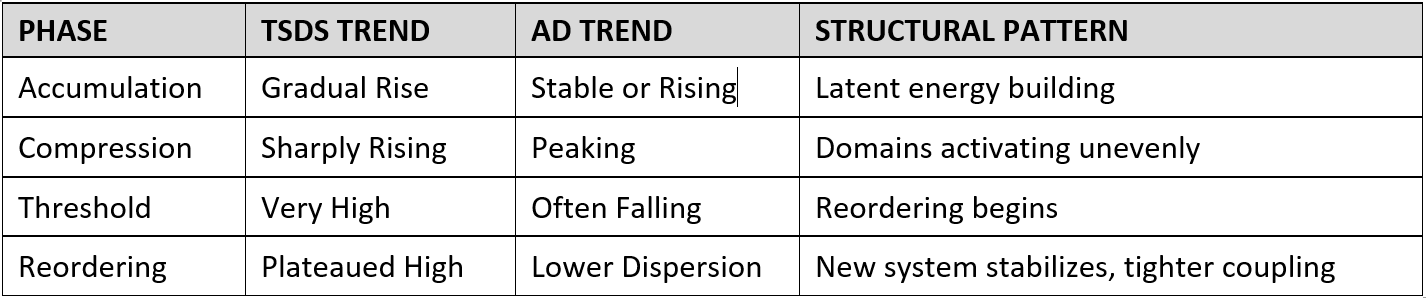

Across these four thresholds, a common dynamic emerges. In each case, a long period of accumulation and incremental change gave way to a phase of compression, when multiple domains of life became active together and started to amplify each other’s effects. During these compression periods, the TSDS gauge climbed to new heights as latent energy built up across society, and AD often spiked as one or two domains initially raced ahead, creating structural imbalances. The existing order grew tighter and more sensitive to disturbances – a telltale sign that the system was nearing its limit. At a critical threshold, small triggers set off cascading changes that the old institutions could not contain. In response, the system underwent a reordering: a rapid (on a historical scale) restructuring of how life was organized, releasing the pent-up pressures by forming a new equilibrium.

Each time, the transition became irreversible once enough domains had crossed a point of no return – whether it was populations too large to feed without farming, or moral ideals too widespread to suppress, or technologies too efficient to uninvent. And each time, a new pattern of life solidified after the turmoil: a higher level of complexity with a new organizing logic for society. Hunter–gatherer bands yielded to agrarian villages; agrarian empires were reframed by Axial wisdom; medieval stagnation gave way to a Renaissance of ideas and connections; and early modern kingdoms were transformed into industrial nation-states.

History shows that systems can endure plenty of linear change, but when multiple transformative pressures converge, they eventually cross a threshold. At that point, continuity shatters. The old equilibrium fails, and a new one forms from the pieces, governed by new rules and structures. Understanding these past crossings – through measures like TSDS and AD and the stories they tell – gives us a clearer picture of how and why civilizations reorder themselves. Each age left a distinct legacy, but the process of compression, threshold, and reorganization is a rhythm that repeats. It reminds us that continuity is not a given; it is earned in each era by how well a civilization can evolve its structure to match the growing energy within. When it can’t, it crosses the threshold – and in that fiery passage, a new world is born.

THE SERIES TO DATE

- When Systems Turn Over

- Why Everything Feels Like It’s Changing At Once

- How Big Shifts Unfold — And Where We Are Now

- Why No Single Force Changes The World

- The Three Drivers That Push Civilizations Across Thresholds

- Reading The Pulse Of A Civilization In Motion

- How The Gauges Were Built: Making Systemic Pressure Legible

- What The Gauges Reveal Across The Ages

Discover more from Reimagining the Future

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

[…] Crossing The Threshold […]

LikeLike

[…] Crossing The Threshold […]

LikeLike

[…] Crossing The Threshold […]

LikeLike