RECAP FROM THE SERIES SO FAR

In the first post, I explored why so many parts of life feel unsettled at the same time: all seven domains of civilization are active and amplifying one another. In the second post, I described the tightening that happens before major shifts — the compression that makes events feel more connected, faster, and harder to absorb. This post turns to the deeper structure beneath these shifts. When we look at history, we see a repeating pattern in how civilizations change shape.

A PATTERN HIDDEN IN PLAIN SIGHT

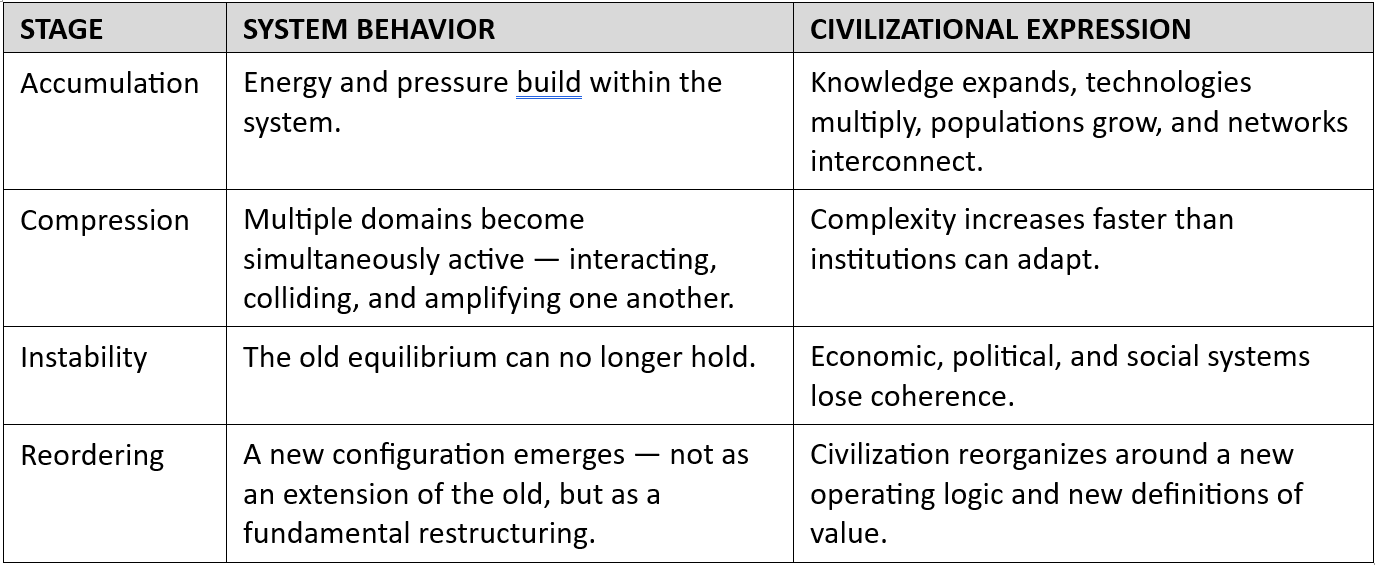

Across thousands of years, the details of each transition vary dramatically, but the structure does not. Whether we look at the Agricultural shift, the rise of Axial philosophies, the Renaissance transformation, or the Industrial revolution, we find the same four-stage rhythm: accumulation, compression, instability, and reordering. These stages help explain how entire ages change form and how we might interpret the moment we are living through now.

STAGE ONE: ACCUMULATION — THE SLOW BUILD-UP OF POTENTIAL

Accumulation is the quiet phase. New capabilities develop, ideas circulate, and pressures grow in the background. Before the Neolithic Agricultural Revolution (~10,000 BCE) fully took hold, accumulation happened through small improvements in cultivation, storage, and seasonal knowledge. Nothing about the era felt revolutionary. Yet each advance added to a growing reservoir of potential.

We find a similar accumulation period before the Axial Age. For centuries, trade networks expanded, intellectual traditions deepened, and early urban centers formed. These slow-moving forces created the foundation for the philosophical breakthroughs that would follow. The Renaissance (14th–17th centuries) also emerged from accumulation: centuries of preserved texts, merchant networks, and the diffusion of classical knowledge — accelerated after the fall of Constantinople in 1453 and amplified by the printing press. Long before Florence bloomed, the ingredients were quietly piling up. Accumulation rarely feels historic, but it sets the conditions for everything that comes after.

STAGE TWO: COMPRESSION — WHEN FORCES BEGIN TO INTERACT

Compression begins when previously independent forces start to reinforce each other. In the Agricultural shift, compression appeared when climate stability, early domestication, and rising population densities interacted. These weren’t isolated trends anymore. They pushed on each other, tightening the system.

Before the Axial Age, compression showed up in the strain faced by early states, trade-driven cultural exchange, and rising social complexity. These forces magnified one another, creating pressure for new forms of meaning and organization. The Renaissance had its own compression phase: emerging scientific methods intersected with expanding trade, new financial tools, and political fragmentation. The result was a tightly coupled system where changes in one domain amplified changes in others. Compression is the moment when a system becomes dense — when pressure no longer stays local.

STAGE THREE: INSTABILITY — WHEN THE OLD LOGIC WOBBLES

Instability emerges when inherited structures can no longer handle the pressures that have accumulated and compressed. During the Agricultural transition, instability took the form of conflicts over land and surplus, early stratification, and governance challenges. The norms of mobile bands could not stabilize growing settlements.

The Axial transition (~800–200 BCE, as described by Karl Jaspers) also had a clear instability period. Older mythic worldviews struggled to hold together expanding, diverse societies. Social unrest, political upheaval, and moral questioning created space for new ideas from Confucius, the Hebrew prophets, the Greek philosophers, and the Buddha. The Renaissance entered instability when its compression collided with rigid medieval structures. Trade expansion, scientific challenge, religious tension, and political fragmentation destabilized the old order. The Reformation and the scientific revolution are clear signals of this phase.

These periods of instability vary in their intensity, but the pattern is consistent: inherited structures strain under pressures they were not designed to handle. The Industrial Age had its own instability: labor unrest, urban crowding, public health crises, and political agitation. Guilds, feudal remnants, and small-scale markets could not handle the velocity of mechanized production. Instability is revealed when a system has outgrown its inherited logic.

STAGE FOUR: REORDERING — WHEN A NEW PATTERN TAKES HOLD

Reordering is the arrival of a new equilibrium. It becomes visible when new institutions, norms, and structures begin to match the pressures of the age more effectively. After the Agricultural transition, reordering took shape in the form of cities, centralized governance, writing systems, property regimes, and large-scale ritual and temple complexes — some of which predated settled farming but expanded dramatically after it — early foundations that later enabled organized religion in the Axial Age.

After the Axial period, reordering produced more coherent philosophies, formalized moral systems, expanding states and more structured political orders, and new understandings of the individual’s place in society. Ideas that once belonged to scattered thinkers became civilizational anchors. The Renaissance reordered Europe around scientific inquiry, new artistic expression, stronger states, and early capitalism. The intellectual and economic architecture of the world began shifting in ways that would define the modern age.

Together, the First and Second Industrial Revolutions (c. 1760–early 20th century) produced an even clearer reordering: mechanized production, urbanization, electricity, steel, automobiles, mass education, corporations, nation-state consolidation, global markets, and institutionalized science — the foundations of modern life. Reordering is not a return to what came before. It is the emergence of a new operating logic — different scale, different speed, different expectations.

WHY THESE FOUR STAGES KEEP APPEARING

Civilizations behave like complex systems. Pressures build, concentrate, spill over, and eventually force new arrangements. The specifics change — the technologies, the population patterns, the resource dynamics — but the rhythm repeats.

This pattern matters because it helps interpret the moment we are living through now. More importantly, it helps all of us interpret it. We are collectively inside a period where pressures across science, technology, economics, society, geopolitics, the environment, and philosophy are interacting at high speed. The signals look familiar. They resemble late compression and early instability — the same phases that preceded past reorderings. Not everywhere, not uniformly, but across enough domains to matter.

Scientific discovery is accelerating. Technology permeates everything. Demographic shifts are redefining expectations. Environmental constraints have entered every conversation. Knowledge travels instantly. Meaning structures are shifting. Geopolitical tensions are rearranging alliances and supply chains. The domains are interacting. That is what defines compression turning into instability.

WHERE THIS POINTS

History suggests that reordering follows periods like this. Not collapse — reordering. The shape of the next architecture is still forming, but understanding the pattern makes the moment easier to read. It becomes clear which structures are under strain, which experiments are emerging, and where new equilibrium might take shape.

CALL TO ACTION

When you look across these transitions, which stage resembles the world today? I welcome your reflections. The next post focuses on why no single domain — not technology, not economics, not geopolitics — pushes a civilization across a threshold by itself. Deep change requires multiple domains moving together.

WHAT THIS MEANS FOR US

This four-stage pattern brings clarity to a noisy moment. It shows that turbulence has structure and that the energy in the system is moving toward something, not simply away from something. Understanding the arc makes it easier to interpret signals and identify which changes matter most. It doesn’t remove uncertainty, but it provides a steadier footing — a way to navigate with perspective, rather than reaction, as the next architecture begins to form.

THE SERIES TO DATE

Discover more from Reimagining the Future

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

[…] like in daily life — the tightening, the pressure, the sense that everything is connected. The third post revealed the pattern beneath these moments: a four-stage rhythm of accumulation, compression, […]

LikeLike

[…] logic is beginning to shift, explored what compression feels like in daily life, and laid out the four-stage pattern that has shaped every major transition in history. Post Four explained why those transitions do not […]

LikeLike

[…] that something in the operating logic of civilzation is shifting. We looked at phase transitions, the four-stage pattern that repeats across history, and the seven domains that structure civilization. The last post […]

LikeLike

[…] to understand how civilizations change. I explored the seven domains that shape collective life, the forces that move within them, the thresholds that mark historical turning points, and the three drivers […]

LikeLike

[…] How Big Shifts Unfold — And Where We Are Now […]

LikeLike

[…] How Big Shifts Unfold — And Where We Are Now […]

LikeLike

[…] How Big Shifts Unfold — And Where We Are Now […]

LikeLike

[…] behind major shifts in history. We explored how change accumulates, compresses, destabilizes, and eventually reorganizes life around new assumptions. We introduced the seven domains that shape every transition and showed […]

LikeLike

[…] How Big Shifts Unfold — And Where We Are Now […]

LikeLike