In a recent insights report, authors Karen Harris, Austin Kimson and Andrew Schwedel look at macroeconomic forces and their impact on labor in 2030. The Collision of Demographics, Automation and Inequality will shape the 2020s – a collision that is already in motion. By 2030, the authors see a global economy wrestling with a major transformation, dominated by an unusual level of volatility. Here’s a summary of these three forces:

AN AGING WORKFORCE

As the global workforce ages rapidly, our authors forecast a slowing of U.S. labor force growth to 0.4% per year in the 2020s, thereby bringing an end to the abundance of labor that has fueled economic growth since the 1970s. Even as longer, healthier lives allow us to work into our sixties and beyond, it is not likely to offset the negative effects of aging populations. This labor force stagnation will slow economic growth, with negative side effects including surging healthcare costs, old-age pensions and high debt levels. On the positive side, supply and demand dynamics could benefit lagging wages for mid-to-lower skilled workers in advanced economies through the simple economics of greater demand and lesser supply – but that leads to their second major force: automation.

AUTOMATION

Advanced automation will accelerate in the years ahead – and the scarcity of labor serves as a catalyst. A significant boost in productivity is likely, but the authors warn of an imbalance between supply and demand: to grow, economies need demand to match rising output. Their analysis shows automation is likely to push output potential far ahead of demand potential. While the impact to jobs is a widely debated topic, most estimates show a significant loss of jobs. The authors estimate that 40 million workers will be displaced, and wage growth depressed for many more workers. They see the benefit of automation flowing primarily to highly skilled and highly compensated workers – about 20% of the workforce. The other beneficiaries are the owners of capital. The existing scarcity of highly skilled workers will grow more acute – pushing their incomes even higher relative to lesser-skilled workers; which leads to the third force: income and wealth inequality.

INEQUALITY

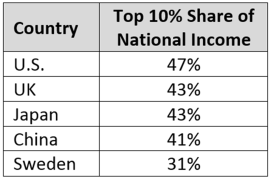

According to the authors, inequality has many possible causes, including demographics, technological change and government policy. They provide data supporting the fact that income and wealth inequality have been growing for decades, reaching or exceeding historic highs in many countries. The chart to the right reflects the current share of pretax national income going to the top 10%.

According to the authors, inequality has many possible causes, including demographics, technological change and government policy. They provide data supporting the fact that income and wealth inequality have been growing for decades, reaching or exceeding historic highs in many countries. The chart to the right reflects the current share of pretax national income going to the top 10%.

According to the authors, the top 1% worldwide have increased six percentage points of share since the global financial crisis – from about 44% of global wealth to more than 50%. An interesting correlation exists between people with higher incomes and their longevity and education level.

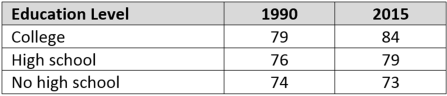

Their longer, healthier lives enable a longer period of wealth accumulation, and more education has an interesting effect on longevity. Between 1990 and 2015, the life expectancy for a 25-year-old in the U.S. across education levels is reflected in the chart above. As we can see, the life expectancy of people without a high school degree declined from 74 years to 73 years. The authors project that by 2030, the life-expectancy gap between an American with a college degree or higher vs. one without a high school degree is expected to widen even further to 16 years.

Their longer, healthier lives enable a longer period of wealth accumulation, and more education has an interesting effect on longevity. Between 1990 and 2015, the life expectancy for a 25-year-old in the U.S. across education levels is reflected in the chart above. As we can see, the life expectancy of people without a high school degree declined from 74 years to 73 years. The authors project that by 2030, the life-expectancy gap between an American with a college degree or higher vs. one without a high school degree is expected to widen even further to 16 years.

OTHER KEY MESSAGES

This report is very well done. I highly recommend it for anyone focused on the future, as well as potential scenarios and their implications. Other key messages from the report:

- Their base-case scenario forecasts that aging populations will depress supply growth as workers move into retirement, but automation will more than compensate for the shortfall by generating higher productivity. Supply growth potential will therefore accelerate. But as automation displaces millions of workers and inequality grows, we will be faced with demand-constrained growth.

- Based on the authors demographic projections, automation analysis and macroeconomic modeling of the US economy, they estimate the potential requirement for approximately $8 trillion of incremental capital investment during the 2020s to achieve the level of automation projected in their base case.

- A key hypothesis in the report is that government intervention may be required to deal with the collision of these three forces and their implications. For example, according to recent data from Vanguard, as of 2017, fewer than half of Americans age 55 to 64 have at least $70,000 in their retirement accounts. Another survey in 2016 by Go Banking Rates found only 26% of those age 55 to 65 had retirement savings greater than $200,000, while 56% had less than $50,000. Most retirees likely will require government transfers if they are to sustain their consumption. Governments, in turn, will require a pool of income to tax to fund the transfers.

- Generational differences likely play a major role in the future. Research from the World Values Survey indicates that support for authoritarian alternatives to democracies is notably higher for millennials in the US and Western Europe than for other recently surveyed generations. In the US, one in six agree it would be better for the army to rule vs. just one in sixteen in 1995. Similar upward trends are seen in Germany, Sweden and the UK. The sharpest rise has come from younger, more affluent millennials. In our context, this suggests that with millennials increasingly at the helm, societies may be more willing to embrace an increased role of government in the marketplace.

The conclusion from this analysis is consistent with my thinking: resilience must become a higher strategic priority. Turbulent times will require us all to be adaptive. The authors hone in on one of our biggest challenges: focus on shareholder value and quarterly results. In their analysis, a focus on financial efficiency at the expense of future competitiveness is dangerous when companies face this much change. Becoming a resilient organization involves investing in an ability to quickly recover from disruptions and regain momentum.

Expect geo-political events beyond the control of any business to replace these concerns with larger issues. For a quick look, take the violent history of the 20th century and multiply by some unknown factor.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] capabilities are difficult to attain in the current iteration of business. Combined with several macroeconomic forces, these drivers make the transition to Business 4.0 inescapable. This transformation therefore […]

LikeLike

[…] wrote about a recent analysis conducted by Bain & Company in an earlier post on the Turbulent 2020s and what it means for the 2030 and beyond. An interesting related exchange on Twitter focused on […]

LikeLike

[…] a matter of fact, they are delaying other life events like employment as well. In a very good Report from Bain and Company, they capture this phenomenon by describing two new life phases: second […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] The world is about to enter a pivotal decade. This decade is likely to be remembered as the launching pad to a very different future. The next ten years are marked by uncertainty, complexity, and an inability to predict how an overwhelming number of Dots Connect to shape the decade. In a 2018 post, I looked at some work by Karen Harris and others that focused on some of the Macro Trends that drive the decade. In the supporting insights report, the authors see volatility emerging from the Collision of Demographics, Automation, and Inequality. These three factors drive a very Turbulent 2020s and Beyond. […]

LikeLike

[…] mile – are a problem expected to get worse as society continues to age in what some call the turbulent twenties. Autonomous trucks solve that growing challenge. The transfer hub model keeps human drivers in the […]

LikeLike